Generalists vs Specialists

Who wins when a bear fights a shark? Depends on where the fight takes place.

I'm quite far removed from my personal peak physical fitness: I used to be able to run a mile in 6 minutes; I now struggle to climb 6 flights of stairs. It's gotten especially bad the past few months as I've struggled with various health issues, especially over the past two years. While I've been working with a personal trainer to help me get back in shape, it hit me: why doesn't personal training exist for decision-making?

I'll share more about what I'm calling "decision training" in later posts, but I think there's incredible potential for using the world of physical fitness and training to inform what healthy practices look like for less tangible pursuits - in my case, decision-making.

The world of athletes and their training programs has inspired many thinkers. David Epstein is the author of Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, where he writes about the differences between generalists and specialists. It's an interesting read that flows well because Epstein uses various case studies to prove his point, beginning with the story of Tiger Woods and Roger Federer.

Tiger and Roger are some of the greatest athletes of all time in golf and tennis, respectively, but had very different paths to getting there. Tiger trained to play golf effectively from the cradle, while Roger only began seriously pursuing tennis in his teens. They're great examples of the archetypes Epstein is speaking about: Tiger is a specialist, whereas Roger is a generalist.

Generalists and specialists each have their strengths and weaknesses, and they thrive in different types of environments. Taking the time to understand ourselves and our environment is critical to making healthy decisions.

We don't all fall neatly into the dichotomy of generalists and specialists. Like most distinctions in life, it's more like a spectrum than a binary. The naming is quite descriptive, but here are some characteristics of generalists and specialists:

Generalists

- Better at strategic thinking

- Jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none

- Less efficient at routine tasks, good with ambiguity

- Cross-domain expertise

Specialists

- Deep expertise in their specialty

- Narrow focus, master-of-one

- Difficulty adapting to change

- Excellent at routine tasks, struggle with ambiguity

Obviously, these aren't exhaustive lists. These characteristics don't indicate the relative value of generalists or specialists, and to be a certain type in one sphere of life doesn't preclude being the other type in other spheres of life. However, most people will gravitate towards one end over the other, much as people are classified into introverts and extroverts.

The beauty of being able to identify where you fit on this scale is that you’re able to identify the environments and conditions that allow you to thrive. Epstein cites the work of Robin M. Hogarth, one of the titans of behavioral economics. He’s one of my personal heroes, largely because we’re animated by the same two questions. Quoting from his website:

Two questions inspire my research: (1) How do people make decisions? (2) How can you help people make better decisions?

One of Hogarth’s big ideas was to distinguish between the two types of learning environments. Kind learning environments are predictable places with consistent rules and patterns - you’ll get instant feedback on how you’re doing in a kind learning environment. A good example of this is a game like chess: the rules are straightforward, and you’ll know when you don’t play well and can quickly improve. Naturally, specialists do quite well in these environments.

The opposite of a kind learning environment is a wicked learning environment, where generalists end up doing better. It doesn’t give you instant feedback and is unpredictable in outcome, with rules and patterns that are quick to change. Most real-life scenarios are wicked learning environments because you don’t really know if the decisions you’ve made are beneficial until much later. If you’re interested in learning more, you can read Epstein’s Substack post about kind vs wicked learning environments.

The main point he makes in his book Range is that having range, i.e. being a generalist, is a better and more predictable road to success in life than being a specialist. I want to highlight a corollary: if we know where we fall on the generalist/specialist spectrum, we can choose to be in environments that are best suited for our success.

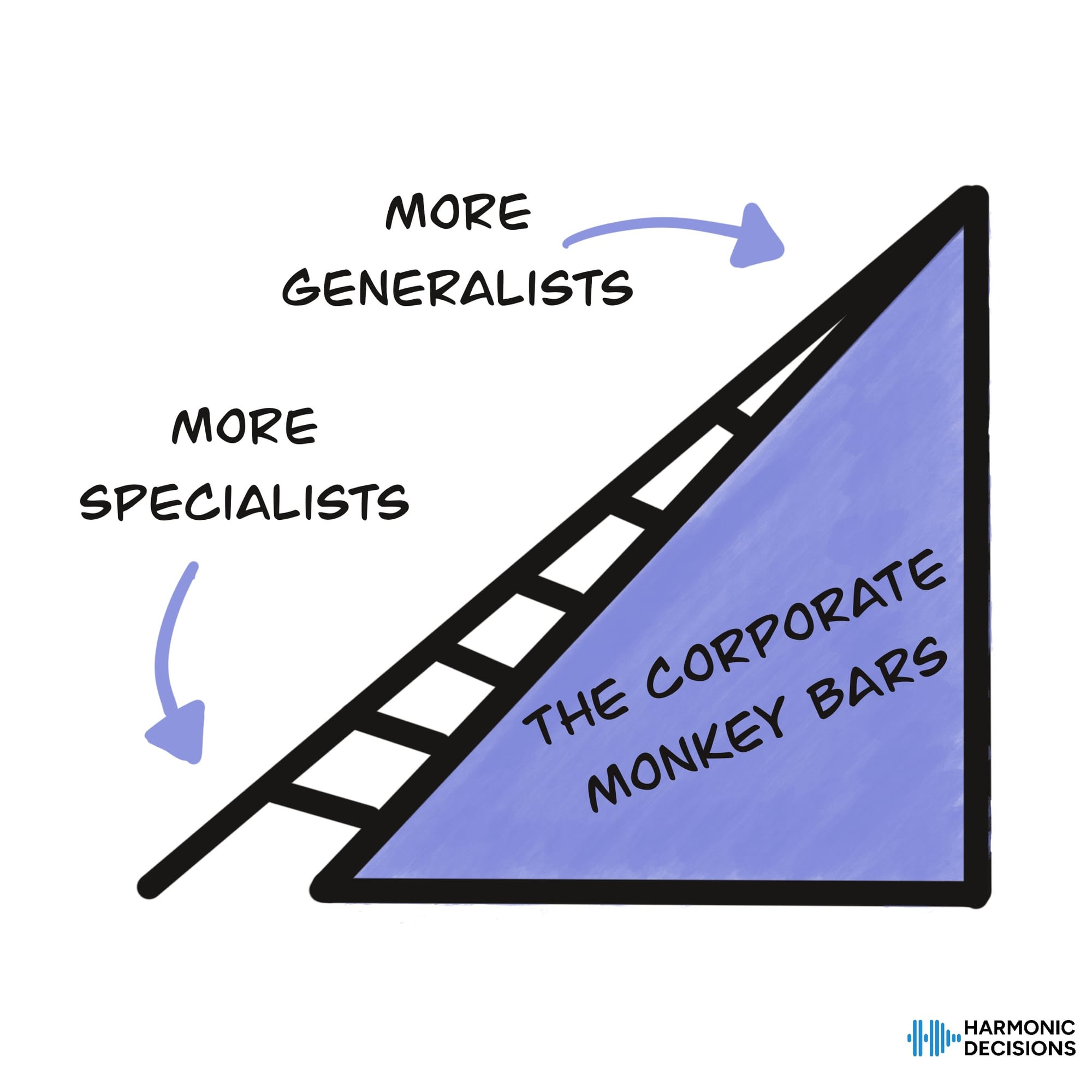

To use an example of how this all plays out in real life, let's look at something most of us are familiar with: the standard corporate hierarchy. One thing I’ve recently realized is that the corporate world isn’t really a ladder - it’s more like a set of monkey bars.

The goal of both ladders and monkey bars is to move from rung to rung. However, while climbing a ladder is largely done on your own strength, monkey bars are crossed by a combination of strength and momentum. Here’s another way to think about it. Strength is the force that directly comes from you. Momentum is the force that's pushing you forward that doesn’t come directly from you but rather the environment's reciprocation to what you've already put out into the world.

A little bit of momentum can compensate for large amounts of strength, although a certain level of strength is required regardless of how much momentum you have. In the corporate world, we can understand your strength to be your specialized skill, whereas your momentum is your network and influence with others.

To characterize the corporate world as a ladder is to cast it as a kind learning environment. The rules are simple: improving the quantitative metrics of your job (writing reports faster, closing more sales calls, making more products) is what allows you to climb the ladder. This is an environment that the specialist thrives in.

However, to rapidly ascend the corporate hierarchy (or perhaps even to just stay at your own level in a competitive industry), we need to harness a force greater than our own strength. At the beginning of a career, when strength is freely available, swinging from bar to bar is easily done. However, as someone progresses in their career, they’ll naturally reach the limits of their own strength. Also, as people age into a lifestyle with more responsibilities, they lose the capacity to develop strength as easily. Rather, their momentum - their network and ability to manage up/down/horizontally or perhaps even playing politics - becomes so much more important.

This is because the corporate monkey bars are a wicked learning environment. The same strategies and rules that have led to success in the past aren’t guaranteed to give future success. It’s not enough to get better at routine, specialized tasks; we also need to improve our ability to deal with ambiguity, think strategically, and understand areas of the business not in our specific domain. This is why generalists do so well in wicked learning environments and are found at higher levels of the corporate hierarchy.

This deeper understanding of the corporate world and its learning environment has been really helpful for my own professional life, but the general principle here is applicable in any situation. We need to find alignment between who we are and the environment that allows us to thrive. We can’t dramatically change who we are (generalist vs. specialist), but we can recognize the environment we’re in and make the necessary changes to set us up for success.